Having published the first article in this series, ”Confessions of a Systems Thinking ‘Newbie’”, I now want to turn my attention to the first true building block of systems thinking, the simple concept called “feedback.” Of course, when I say feedback, you may immediately start thinking of the meaning of that term in light of various contexts in which you have encountered that before, especially in terms of coaching and/or your performance appraisal experience in business. You may associate “feedback” closely with the terms “positive” or “negative” because you may have experienced positive or negative feedback in those familiar contexts. I would absolutely expect you to have that contextual view of this word.

The fact is that if you are asking someone to give you a response (effect) to some action (cause – like how you are performing or managing, etc.), then the term is being applied correctly. If you are just asking someone to share how they are feeling in general or their view of how things are going, then in reality you are not receiving feedback, but instead, just information about a situation or current state. Why am I droning on about what seems to be a technicality? Because to truly understand the overall principles and usefulness of systems thinking, understanding this very central concept is essential.

What is Feedback?

If you look in a dictionary or perhaps browse Internet sources such as Wikipedia, you will quickly discover that the term  “feedback” has deep roots in the fields of science and is a very specific technical term used to describe forces within a closed system. Feedback is an essential part of a chain of cause-and –effect events that form a circuit or loop, where forces “feed back” into itself.

“feedback” has deep roots in the fields of science and is a very specific technical term used to describe forces within a closed system. Feedback is an essential part of a chain of cause-and –effect events that form a circuit or loop, where forces “feed back” into itself.

This diagram, which you can find on Wikipedia, identifies two entities, “A” and “B”, and forces or actions between them that form a “feed back” loop. Actions performed by A upon B generate a responsive action from B onto A. There is a cause and effect, and then another loop of cause and effect, and so on, that simply continues to loop. This is the origin of the term “feedback” whether you are talking about something mechanical, or within the context of living systems, which is an appropriate context for thinking about your own organization.

The Two Types of Feedback in Systems Thinking

Within this context of a business organization and systems thinking, you will find two types of feedback that are called “reinforcing feedback” and “balancing feedback.”

Reinforcing (Amplifying) Feedback

The great thing about reinforcing or amplifying feedback is that this type of force is usually quite obvious and easy to observe. Using your car as an example of reinforcing feedback in a mechanical system, when you push down on the accelerator, you are ultimately causing the engine systems (a closed mechanical system) to increase the revolutions and create more power and faster speed. Combustion engines use a reinforcing feedback loop to increase (amplify) revolutions and power.

What about reinforcing feedback in business? You launch a new product or service. Initial customers are thrilled and satisfied and soon word of mouth spreads (verbally and through social media) and this generates more sales in what one might call a “snowball effect” or in today’s world perhaps a “viral effect.”

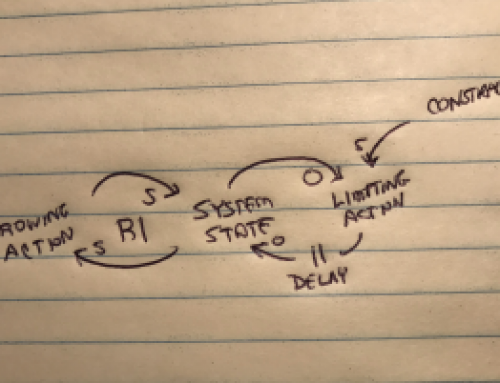

This is a perfect example of reinforcing feedback in systems thinking and can be represented by the causal loop you see in Figure 1. The symbol in the middle of the loop is the standard symbol used to identify this as a “reinforcing” loop.

At the same time, you must remember that this reinforcing or amplifying force can work to accelerate decline. This type of reinforcing feedback may be a little harder to detect but if you see some key indicators in your business declining steadily, the first thing you will want to examine is whether there is some reinforcing feedback force driving that decline.

In a recent post, I mentioned the airport car service that created some serious problems for their business through a lack of planning in regards to handling a Groupon offer. What they like discovered as time passed is that there was a growing number of poor reviews on various social media sites that acted as a reinforcing feedback force that contributed directly to revenue decline. This is a great example of the two sides of this type of force. A positive word of mouth trend can be a reinforcing feedback that drives business “up,” but the same reinforcing mechanism (word of mouth) can be a reinforcing feedback that drives business “down” (see Figure 2) when the content is negative, thus “reinforcing” that others should not use your business service.

Balancing (Stabilizing) Feedback

The examples of reinforcing feedback I have covered so far assume there is no force at work to stabilize or balance the system. These reinforcing feedback loops have cause and reaction that reinforce each other and give that amplification or growth results. That brings us to this discussion of the second type of feedback in systems thinking – balancing or stabilizing feedback. Balancing feedback exists in a closed system that seeks to balance itself, meaning where there is an explicit or implicit goal or natural level of stability. If you consider free market economies or even a democracy, these are closed systems that seek balance and stability through cause and effect (e.g., supply and demand, elected officials/actions and democratic elections and voting). These systems work in a way that seeks balance, but certainly experience ups and downs so to speak -like control, reaction, over-control, over-reaction, control, reaction, etc. The point is that almost all systems naturally seek some type of balance. You won’t see growth or decline without end, spiraling addiction without balance of consequences, oppression without eventual revolution – you will find naturally balancing or stabilizing forces at work.

A more practical mechanical system example can again be found in your car in the form of cruise control. You use cruise control when you have a goal in mind. You want your car to maintain a specific speed, say, 65mph, so you set the cruise control at that number. However, when you really think about how your car responds to this request to maintain that speed, you realize that it is a balancing feedback loop. Figure 2 is a simple representation of this balancing feedback loop. Your car cannot possibly remain exactly at the “Desired Cruise Speed” due to changes in the grade of the road. As you go up a hill, you fall short of that goal creating a “Speed Gap”, the cruise control communicates with your car’s acceleration control to apply more reinforcing feedback (accelerator) to “Adjust Speed.” Your car accelerates and this closed loops repeats over and over again accelerating or coasting as needed, constantly measuring the speed gap against the desired speed to maintain the desired speed. One important fact to consider in a balancing loop is that it is almost impossible to make adjustments that keep you “exactly” at the desired goal. There are always adjustments going on, sometimes subtle and sometimes not so subtle. Sometimes a system misses the mark a little and sometimes a lot depending on the adjustment. This is especially true when a “delay” is present in the system. We will discuss “delays” in our next installment.

While reinforcing feedback is normally quite easy to recognize and apply in business, I have found that many leaders either have trouble recognizing this second type or do not take the time to systematically look for and evaluate this feedback. Of course, some forms are more recognizable than others.

Example System At Work

Market saturation is an example of balancing feedback as a limit (see Figure 3). The first thing to notice is that this system includes our first example of reinforcing feedback. There is a reinforcing loop in place that is generating more sales due to positive word of mouth. However, now there is a balancing feedback loop at work that is applying a balancing or stabilizing force in terms of a limit in the number of available customers (i.e., customer market size). As you approach market saturation for a product or service, sales growth declines due to that balancing force (the limit) and will certainly continue to decline rapidly if the market size is indeed finite. No reinforcing feedback loop can overcome that finite balancing feedback force (an actual limit in the number of people that can purchase).

A limit is an obvious form of balance. What are other types of balancing feedback forces? In a software implementation project, lack of adoption is almost certainly a sign of balancing feedback resisting the reinforcing feedback of management desire, training, instruction, and directives. There may be resistance to using the new software because of loyalty or preference to a previous method. There may be unrecognized (by those implementing software) unmet needs in the actual functionality that is creating a “gap” and balancing feedback as people have to “work around” those missing pieces. There may be apathy due to past failed projects. As in the above system, you could create a diagram that shows the reinforcing feedback at work for implementation and also one or more balancing feedback loops that exist that are limiting or slowing the system down and preventing continued progress.

Hidden Implicit Goals

Before moving on from this concept, there is another fundamental key to understand as part of balancing feedback. I stated that balancing feedback exists where there is a goal, a specific state that exists or is desired. The cruise control example is an explicit goal. Market size certainly is an explicit state or limit that can be observed and considered (and should be). What about implicit goals? The software implementation example revealed a few implicit goals that were at work that may have been less obvious. Software users may have been considering “loyalty to and happiness with” the current process as an implicit goal. Their goal was to keep what they already had. Or perhaps the goal was “do nothing” as in apathy. It is important to see these desired states as goals that exist in a balancing feedback look to fully understand why you observe certain behaviors that are seeking to maintain that goal (that balanced state as they see it). Identifying implicit goals is a key success factor in utilizing strong systems thinking skills.

Reading the Charts

A quick tip that I want to share relates directly back to something you likely do regularly – look at financial charts or other types of production or workflow charts. Below you see three charts that I deliberately left a little vague in terms of the x and y axis.

This is Just Getting Good

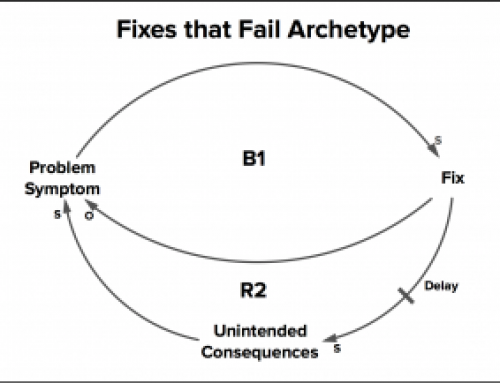

Given this discussion and these examples, you may be saying, “well, of course I think about those things” and as a competent leader you likely do have some built-in intuition about they way some “systems” are at work in your business. You may even stop and spend time reflecting on what barriers you may encounter to success. However, as we continue to learn more about systems thinking and these concepts, my goal is that you see the great value in formalizing your systems thinking to the point that you at least roughly hand draw some diagrams or create a forma list of the possible forces at work within your systems. This ensures that you spend more time reflecting on the “whole” system ahead of time to eliminate unexpected or unintended consequences.

In this post, I have introduced you to the basic concepts of reinforcing and balancing feedback, the type types of feedback present in all closed systems. This is where the fun begins! Our next post will examine the concept of “delays” and how this concept represents the slippery serpents that can easily lead you astray in making necessary adjustments in your system. From there we will move on to the topics of leverage and then to explore the archetypes that guide all systems thinking.