In my last post, Raise Your Competitive Thinking IQ: Introduction to Systems Thinking, I laid the foundation of “why” systems thinking is so relevant and important for today’s business leaders and decision makers and also touched briefly on “what” systems thinking is all about. In this post, I want to begin a short series covering the building blocks of system thinking. In this series, I want to cover:

- the blocks and keys to unlocking systems thinking

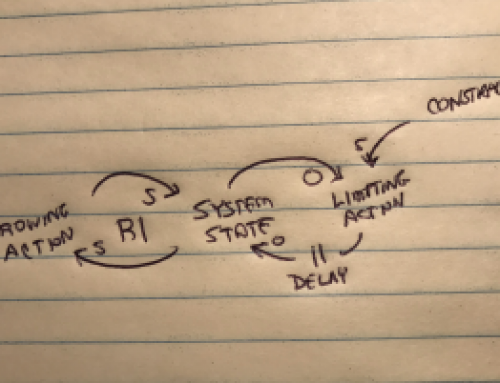

- the obvious and hidden forces – “feedback forces”

- the folly of the impatient and short-sighted – “delays”

- the secret weapon – “smart leverage”

- the predictable and repeating patterns – “archetypes”

What you are going to discover is that while these remarkable concepts which have arisen from the study of many across various disciplines of study including engineering, physical science, social sciences, and management will resonate with you quickly as concepts that are completely sensible and quite frankly, just plain common sense. Yet, as you read the full series you will also perhaps wonder why so many business leaders and decision makers fail to take advantage of this very common sense discipline. For that reason, I am going to start this first post in the series with a quick look at what may get in the way of true systems thinking, and key acknowledgements to keep in mind that unlock systems thinking.

Unintentional Blocks to Systems Thinking

As I said, the more you learn about the building blocks of system thinking and what they can do to improve your decision making process, the more you will wonder why you and so many others may have failed, or even continue to fail in using this discipline and set of skills. I want to approach this from two completely different sides of the coin. First, I would like to give you a quick list of what gets in the way. Then, I would like to give you a list of things to keep in mind that will prove helpful in prompting you to invest further in deploying and coaching systems thinking for many of the decision processes you face.

If you have never fully discussed systems thinking with your staff, or actually used this discipline in decision making, then why haven’t you? There is no judgment intended in this question. I have managed people and led business units for over twenty-five years and only recently discovered that I was “accidentally” applying many of the learning organization and specifically, systems thinking principles in practice. In fact, that is why I am so passionate about this practice and writing. I want to deliberately utilize and teach systems thinking concepts as well as concepts from the broader “learning organization” framework. So, perhaps the best way to answer this question is to first give you the reasons why I was not using systems thinking.

- I knew nothing about the formal discipline of systems thinking.

- As a leader, I believed that I was a “big picture” thinker, and likely did get a lot of the “whole” view intuitively, but again, had no formal knowledge of the full systems thinking discipline.

- I worked in some environments where the desired outcome of decisions was predetermined by rather narrow top-down senior management directives (e.g., cut costs to drive higher profit margins, sell more product in the next quarter, restructure to do more with less people) and thus, had to focus on short-term solution thinking and faced decisions from a pre-determined vantage point.

- When moving to a new business unit, I applied my past experience/best practices to recreate success I saw in the past. My expectations and, also decisions, were based on the past results.

While this is not an exhaustive list of some of my own thinking that may have blocked or inhibited systems thinking, these likely seem a bit familiar to you as a business leader. These are not uncommon and certainly do not represent completely bad practices. All good business leaders have intuitively adapted and developed thinking habits based on their best view of experience, in seeking to see a bigger picture, and in light of the current goals within their own organizations. The goal then, in presenting this series on systems thinking, is to introduce you to a more disciplined approach to seeing the “whole” picture and developing the very best “whole” thinking – systems thinking – around any decision given the short-term and long-term goals and challenges.

Unlocking the Idea of Systems Thinking

Starting with the reality of how you think today, what are going to be the keys to unlocking the power of systems thinking? I apologize now for a bit of repetition from my introductory article, but I believe it is important to put all of these in one place and this requires reviewing one or two of those ideas in the following list of keys that I believe will help you unlock this opportunity to make systems thinking tools a part of your every day management practice. As you begin reading this series presenting the key concepts and tools of systems thinking, it will be helpful to keep in mind the following:

- Acknowledge that gathering and understanding all of the detailed facts/information relating to a decision (understanding the detail complexities) is not the same as exploring and understanding the dynamic complexities (realistically seeing the subtle forces at work – what new forces emerge that reinforce or limit your decision – and fully understanding the implications of your decision over time).

- Acknowledge that cause and effect are not always closely related in time (past, present, and future) and proximity (affecting immediate team or other parts of the system), and thus, represent a key dynamic complexity to be considered.

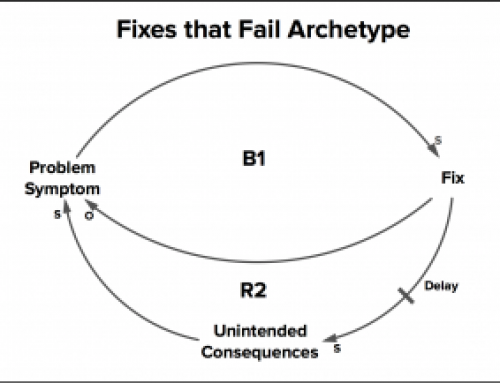

- Acknowledge that the most obvious and likely “quickest” solution that generates short-term results may not be the true leverage point and also set in motion a spiral of unintended dependencies or consequences that cannot be “undone” easily.

- Acknowledge that some decisions simply shift the problem to a different position in time or force a new decision in the future to actually solve the problem.

- Acknowledge that you face decisions today that are simply a result of decisions made in the past and a cycle that has not yet been broken through dealing with the root of that problem cycle.

- Acknowledge that when situations arise where the solution seems to always need or demand “more” of one thing, you may be completely missing the real problem – the force that is limiting progress and requiring “more.”

- Acknowledge that decisions intended to push growth beyond the natural growth rate that is intrinsic to the market will predictably have a “kick back” of unintended consequences due to unnatural system disruption. You simply cannot squeeze blood from the proverbial turnip (a variation on the acknowledgement directly above regarding demanding “more”).

- Acknowledge that the highest leverage (smallest changes that can product the most lasting positive results) is usually the most nonobvious, difficult, leverage to find.

- Acknowledge that you can likely have both the short-term and long-term results you are looking for, but not simultaneously and not likely to the same degree. You have to accept and embrace the connectedness and interdependency of the two and dismiss any idea of fully achieving both at the same time by doing the same things.

- Acknowledge that the structure of your organization may limit your view of the whole system (internal and external parts) and the full dynamics of decisions.

- Acknowledge, as Peter Senge says, in systems thinking there is no separate “other” to blame. In other words, you and all of those involved are part of the whole single system that must be considered.

You Are Ready

Armed both with the confessions of one who failed to fully embrace systems thinking while doing his best to lead in good decision making and also with this list of acknowledgements to ponder as we closely examine system thinking building blocks, concepts, and tools, you are now ready to learn how to weave systems thinking into your ongoing decision making process and overall leadership skill set. I recognize that some of those “acknowledgements” seem a bit mysterious without concrete examples, and that is quite deliberate at this point. It’s best to give you those to digest now and as we work through the series to clarify their meaning and impact with real-world examples of the truth that each brings to light in regards to systems thinking and good decision making. The next post in this series will tackle both the obvious and hidden forces called “feedback” in the systems thinking framework.